Women of Bruce – Part 5 —

Sisters of Robert Bruce: A Tale of

Two Isabels.

When you really get deep into

genealogy you run into a stumbling block of reused names. I have 37 Robert Bruces in my family tree. Nearly as many Patrick Dunbars and Hugh,

William and James Montgomeries. I understand

that men want sons to carry on their names for immortality. Only, sometimes it isn’t just the men’s

names, which provoke the need to be careful in charting your ancestors—it can

be the women, too! Take the name

Margaret—I have over 1000 of those.

Elizabeth? Oh, yeah! 1333 in my tree (and counting!). And Isabel/Isabella/Isabelle/Isobel?—406 and

many belonging to the Bruce family. Both

of Robert Bruce’s grandmothers were named Isabel—Isabel de Clare and Margaret

Isabel FitzAlan Stewart. His paternal

great-grandmothers were Isabelle of Huntington and Isabel Marshall, countess of

Glouster, Hertford, Cornwall and Poitou.

Robert married his first wife—Isabel of Mar. He was crowned by Isabella Macduff, a cousin. But to really confuse matters he had two

sisters by the same first name!

Yes, this tales of two ladies

named Isabel is a study in frustration and chaos. Once more, we are forced to wade through

incorrect information, details—or lack thereof— about two different women

historians so casually dismissed, or merged into one. They are not

the same female! Genealogists have

confused, mixed up, or blended the two Isabels until they are a blur, and we

are left scratching our heads as to why they simply don’t recognize these

ladies are two entirely different sisters of Robert Bruce.

Isabella Kilconquhar Randolph

Through his parent’s marriage,

Robert Bruce had seven sisters, with only five living to adulthood—Isabel,

Maud, Christian, Mary, and Margaret.

However, often overlooked—he also had an older half-sister from his

mother’s first marriage. While she

wasn’t a Bruce by name, she was still his sister, and she gave birth to one of

the fiercest warrior heroes Scotland has ever known—Thomas Randolph, 1st earl

of Moray.

Both women shared the same

mother—Marjorie, countess of Carrick, in

her own right. (I have written about the dashing Marjorie in my previous

articles). They had different

fathers. Both men went off to join the

9th Crusade, raised by Lord Edward, duke of Gascony. And both became close friends. The first Isabel—Isabel Kilconquhar

Randolph—was the daughter by Adam de Kilconquhar. Occasionally, you see her referred to as

Isabel Martha Kilconquhar, or Isabelle of Carrick, some mistakenly call her

Isabel Bruce, and sadly, maddeningly, some do their best to ignore this

daughter all together. She has a

wonderful heritage, so she should be recognized as existing and not bundled

into a generic “Isabel Bruce” label.

Marjorie Carrick married very

young to Adam, son of Donnchaidh de

Kilconquhar. Evidence shows that Adam

hailed from Fife and from the ancient Clan of MacDuff. His grandfather was Adam, son of Duncan, earl

of Fife. Adam’s mother was an unnamed

woman from Clan Comyn (I think through process of elimination that she was

likely Johanna Comyn, daughter of Richard Comyn and Eve Amabilia Galloway). He had a half-brother, William Comyn, who

took his mother’s surname and was named in a papal appointment as the bishop of

Brechin in January 1296 (2/156/3 Theiner,

no. 350 and. 2/147/23 Theiner, no. 262). Ancient and impeccable lineage, but then

the man who received Marjorie in marriage would have to be worthy of a woman

who came from blood royal. Adam appears

to have enjoyed the favor of the Scottish king, Alexander III, so small wonder he won her

hand. In wedding Marjorie, Adam became

the 3rd earl of Carrick, jure uxoris. Documents of the period show him using the

title of earl of Carrick. Still, the

title was little more than an honor, for while Marjorie was the heiress of

Niall, 2nd earl of Carrick, her father had set the real power within the clan

to follow his nephew, Lachlan. We don’t

know if Adam chafed at being earl in name only for he didn’t stay on the scene

long. Shortly after wedding Marjorie, he

joined the Crusade, leaving his young bride at home at Turnberry Castle, either

pregnant or with her newborn daughter, Isabella. Within a year, Marjorie was a widow, due to

Adam dying of a wound contracted in a battle in the Holy Lands.

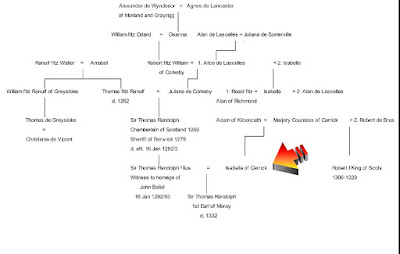

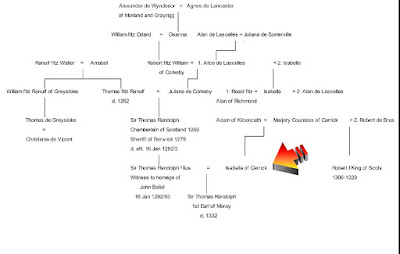

(Tree showing the Randolph, Bruce and

Kilconquhar Lines)

Adam charged his close

comrade—the handsome lord of Annandale, Robert Bruce—to carry the tides of his

demise back to his lady wife. It is

legend how he did just that, and as he made to leave, Marjorie had her

men-at-arms capture Annandale and keep him hostage until he agreed to become

her second husband. Obviously, the lady

was tired of men deciding her fate. King

Alexander III was upset they had dared wed without his grace and

permission. In punishment, he seized

Turnberry Castle. Since Alexander did

not fine Annandale or seize his property, it clearly demonstrated the king laid

blame solely at Marjorie’s feet. Most

likely, Marjorie turned on her charm and soothed the king’s ruffled feathers,

because he turned the castle back to the Bruces a short time later, and just

fined Marjorie one hundred pounds for daring the umbrage.

The marriage was a happy one, and

within the year, Marjorie gave birth to another daughter—which she promptly

named Isabel! So, she now had two small

daughters by the same first name. Why

would Marjorie name both daughters Isabel?

Well, to honor her mother is one possibility—Margaret Isabel FitzAlan

Stewart, countess of Carrick, daughter of Walter Stewart, 3rd High Steward of Scotland and Bethóc nic Gille Chris of Angus. Or since she named her first daughter after

her mother, she was naming her second daughter after the mother of her

husband—Isabel de Clare. Whatever the

motivation we now have two daughters with the same name.

Since Adam was gone, barely a

ghost in people’s memory, and the two little girls were not that far apart in

age, I wonder how muddled their lives became as they reached marriageable

age. Oh,

you are Isabel Bruce? No, I am the other Isabel—not a Bruce. I am unsure if not being a Bruce hurt Isabel

Kilconquhar’s chances at making the best marriage possible. Still, she didn’t do too badly. She married Sir Thomas Randolph, Chamberlain

of Scotland (whose father was Thomas of Strathnith, and who had also been a

Chamberlain of Scotland). Thomas’ mother

was Juliana Kilconquhar of Moray. Since

her parentage is sketchy at best, it’s not hard to assume this she might be

aunt or cousin of Isabel?

Her marriage to Sir Thomas saw

her wed to a very powerful man. As the

Great Chamberlain, he had jurisdiction for judging of all crimes committed

within the burgh, and of the crimes of forestalling (an antiquated term for a

merchant buying his way into a market.

In effect, Thomas was Justice-General over the burghs, and held Chamberlain-ayrs every year for

that purpose; the form whereof is set down in Iter Camerarii. He was a

supreme judge and his decrees could not be questioned by any inferior

judicator. His sentences were to be put into execution by the Baillies of the

burghs. He also settled the prices of provisions within burghs, and the fees of

the workmen in the Mint. Thomas Randolph

was a man of extraordinary parts, and served both Alexander II and Alexander

III. He also aided Robert Bruce “The

Competitor” in his legal bit to be made king of the Scots. Thomas held great favor with Alexander III,

who made him lord great chamberlain of Scotland in 1269, an office which of he

enjoyed till the 18th Aug. 1277. He also

worked as the king’s personal attorney on many matters. Also, the man loved to sue anyone and

everyone. The Scottish court documents

show Thomas bringing lawsuits against dozens of lords and ladies over matters

of estates, properties and inheritance not fulfilled.

Thomas and Isabel had three

children—Nicholas, Thomas and Mabel Isabella.

(Another Isabel! LOL). Mabel

Isabella went on to wed Sir Gilbert de Hamilton, who was one of the seven Royal

Knights or bodyguards for Robert the Bruce.

It was Hamilton who gave the funeral oration at the burial of King

Robert the Bruce at Dunfermline Abbey.

Tower of London

Nicholas, the eldest Randolph son, was

captured at the Battle of Dunbar 1296 and taken to be held prisoner in the Tower

of London. King Edward wrote to the

sheriff of London concerning the payment of expenses of Scottish prisoners in

the Tower, including “…William, earl of Ross, Andrew de Morpenne, John de

Mowbray, Nicholas Randolph, the king’s enemies….” recorded by John of Droxford, keeper of wardrobe of King Edward I, 6th

November 1297. (Docs., ii, no. 481).

Odd, in September of 1296, his father was sent to France by King John

Balliol. These two references are the last

we hear of either man. It is reasonable to assume within months after

Longhanks’ letter concerning the payment for his keep that Nicholas died. I

haven’t found any written release, and the conditions of the release, so my

guess is he died in prison. Many of the

hundreds of Scottish nobility had been returned to Scotland long before this,

so it is unusual Nicholas, the son of such an important man, was still being

held.

Isabel’s younger son, Thomas, was

originally sworn to Edward Longshanks, and after fighting for the English, he

was captured in 1306 and brought before her brother, Robert. Arrogant, and unbowed, he taunted his uncle

for engaging in guerrilla warfare instead of standing and fighting in pitched

battle. Failing to take umbrage, Robert

persuaded his nephew to change sides again.

Thomas went on to become one of the king's most important and trusted

captains, the 1st earl of Moray, regent for Robert’s son David II, and

eventually becoming Guardian and Chamberlain of Scotland. He was a distinguished diplomat, just as

formidable an opponent at court as he had been a warrior on the battlefield.

To add to the growing list of

Isabels—Isabella’s granddaughter was Agnes Randolph Dunbar, countess of

Dunbar, who held the siege of Dunbar Castle.

I wrote about Agnes’ colorful exploits in A Tale of Two Women and One Castle - The Ladies of Dunbar—Part Two—Agnes Randolph. However, son Thomas

had another daughter, which he naturally named Isabelle. And, oh, his wife’s name?

—Isabel Stewart of Bonkyll.

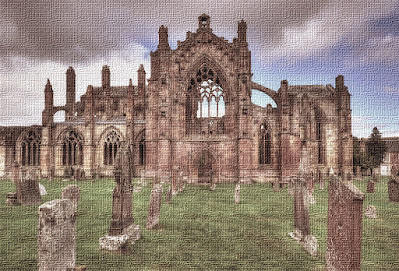

Isabella Kilconquhar Randolph

lived until her early eighties. She

outlived her husband and both sons, dying less than two years before her

daughter. She was laid to rest beside

her beloved husband in Melrose Abbey, and next to his father Thomas fitzRanulf

of Moray and mother, Juliana Kilconquhar.

Queen Isabel de Brus Magnússon’s Coat of Arms

Isabel de Brus Magnússon—the other Isabel was a full sister to Robert Bruce. She was born less than three years after her

older half-sister with which she shared a name.

She was the first child of Marjorie Carrick and Robert de Brus. And

though her brother may have been destined to become a king, at the age of

twenty-one this Isabel became a queen before him!

Ever mindful of cementing the House

of Bruce into the royalty of Scotland and her allies, Robert Bruce, lord of

Annandale, arranged a marriage for his eldest daughter to the king of

Norway. In 1293, Isabel traveled with

her father to Bergen where she wed to King Eric Magnússon II of Norway in true

royal fashion.

The last surviving son of King Magnús

the Lawmender, Erik was given the

title of king at age five by his father.

Magnús had intended for his son to co-rule with him, but before this

could be arranged King Magnús died. Erick was then crowned sole ruler in the

summer of 1280. A year later, at age

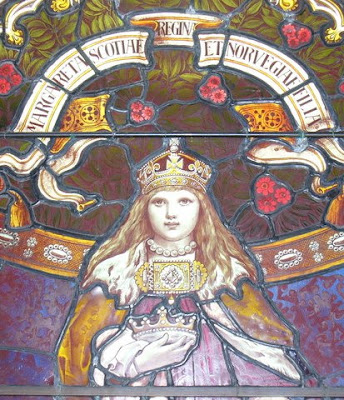

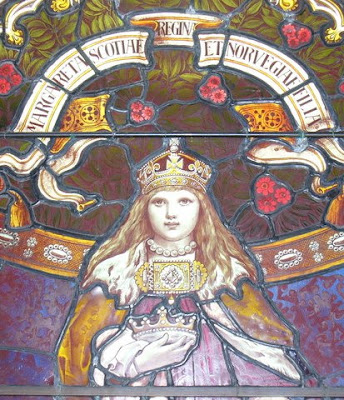

thirteen he married twenty-year-old Princess Margaret of Scotland, daughter of

King Alexander III. Tragically, Margaret

died two years later giving birth to a daughter also named Margaret, who would

go down in history as the Maid of Norway. After Alexander’s death—leaving no male to

follow him— this small child, not even eight-years-old, soon grew to be the

center of unparalleled political maneuvering, since she now was the true heir

to the Scottish throne.

In 1286, she became the child Queen

of the Scots, though she had never set foot in Scotland and was never

inaugurated. And just as quickly, she was

betrothed to Edward I’s son. Longshanks

wanted her wed immediately to Edward of Caernarvon, for in his vision his son

would then rule Scotland as king through her.

The Guardians of Scotland resisted this plan, and after much choreography

and negotiating, the nobles set out to collect the wee lass to bring her home—and

under their control before Edward decided to fetch her himself. Edward wasn’t above executing such a power

play, and they knew if that occurred the English monarch would never set her

free. Alas, a storm blew her ship off

course, and they were forced to land at St. Margaret’s Hope, South Ronaldsay on

Orkney. Odd bit of fate. The village

was named after St. Margaret of Scotland, the wife of King Malcolm III. We hope the saint took pity on the small

child who bore her name, for she died shortly after making it to shore.

The incident sparked one of the

biggest legal battles in Scottish History —The

Great Cause. Seventeen claimants

vied to be the next king of Scotland.

Isabel’s grandfather—Robert Bruce, 5th lord of Annandale—was

a leading contender. Even the man who

would soon be her husband within a year, as King Erik of Norway had tossed his

name into the hat, so the speak,

claiming he held the right to rule through his deceased daughter.

Monument to the rules of Norway, including a listing

for King Erik, his wife, Princess Margaret of Scotland, and their daughter, Margaret, Maid of Norway- Bergenhus Fortress, Bergen, Norway.

Isabel had arrived in Norway, a well-propertied

woman and bringing riches to her marriage, bespeaking she was a woman worthy to

be a queen. Her dowry and trousseau were

recorded at the time by Weyland de Striklaw, an English nobleman employed by the

king. Striklaw noted the delivery of the

goods for Isabel’s trousseau: precious

clothes and furs, 2 golden boiler, 24 silver plate, 4 silver salt cellars and

12 two-handled scyphus (soup bowls) for her new household. The marriage seemed to agree with her, and

she developed a deep love for her new country and the church at Bergen. Almost four years later her daughter Ingebjørg

Eriksdottir was born. However, the

marriage ended abruptly when Eric died 15th of July 1299.

Bergenhas Fortress, Bergen, Norway

Widowed at the age twenty-six,

Isabel could have returned home to the Bruces, yet she stayed in Norway, and in

spite of the insecurities that came with widowhood, Isabel was in no hurry to

remarry. There were some motions of a

marriage in 1300. Not for Isabel, but

her infant daughter. Though Ingebjørg was

only three- years-old, Isabel moved ahead with the plan to marry her child to Jón

Magnússon, earl of Orkney and Caithness, the betrothal recorded in the Icelandic Annals. Magnússon, by nature of each earldom, was a

subject of both Scotland and Norway. Most believe this was a desperate attempt on

Isabel’s part to find a protector for her daughter, and one aligned to the

Bruce’s cause and able to affect influence in Norway as well. Nevertheless, the wedding never took place as

Magnússon died soon after the contract was recorded. Perhaps her fears soon

proved unfounded for there were no further attempts to find a protector for

either herself or her child. Instead,

Isabel settled into life as queen dowager.

As a queen consort scant

information remains on Isabel’s life. On

the other hand, as queen dowager her days are better chronicled. Queen Isabel participated in many official

events and ceremonies, and clearly did not lack sway. Her presence was recorded with the new king—King

Haakon (Erik’s brother)—and his wife on many court occasions. It was documented she was with the royal couple

at the inauguration in 1305 of Bishop Arne Sigurdssön, the new bishop of

Bergen. Though her husband has been

slanderously nicknamed “priest hater”, Isabel had a good relationship with the

clerical powers in Bergen. She made

large donations in 1324 to the local church, and in return she received several

houses from the bishop to provide an income for the rest of her life, leaving

her independent in a time women rarely had this sort of freedom.

In 1301 a woman arrived at Bergen

on a ship from Lübeck, Germany. Quite

bizarrely, she claimed to be the dead Margaret all grown up. She accused several people of treason for

trying to hide the real queen of the Scots. Her story detailed that she hadn’t died on

Orkney, but had been sold into slavery by Tore Haakonsson's wife (also named Ingebjørg),

and then sent to Germany where she had married.

The people of Bergen and even some of the clergy vigorously took up her

cause, in spite of the fact that the late King Erik had identified his dead

daughter's body. Even more damning—the

woman appeared to be about forty-years-old, whereas the real Margaret would

have been seventeen had she lived. After

a much followed trial, she was burned at the stake for treason at Nordnes in

Bergen in 1301, and her husband was beheaded.

Whether Isabel attended any of the trial isn’t recorded, thought I’m

sure she was aware of the proceedings.

Isabel’s quiet power likely helped

the rise of Weyland de Striklaw—who we already met when the goods for Isabel’s trousseau were unloaded. After Jón Magnússon’s death left the marriage

for her daughter moot, Isabel’s patronage may have been the reason for his rising prominence—and

possibly to her benefit. Striklaw somehow managed to become guardian for

the earl’s successor, and gained control of the administration of Orkney and

later Caithness. Little direct evidence can

be found for Isabel being responsible with the man’s rise from exiled

Englishman to one who controlled two earldoms.

Still, that command over Orkney and Caithness—earlships she had intended

for her daughter—could be taken as an indication of Isabel’s discreet political

activity after her husband’s death.

There is intimation that she was

a mediator in the negotiations between Norway and Scotland, regarding the dispute

of ownership of Orkney and Shetland when in 1312 the Treaty of Perth was reaffirmed. Another is the occasion of her apply to King Haakon for a pardon of a prisoner 1339.

During her sister Christian’s

imprisonment by Edward I, the two sisters exchanged letters. Isabel even sent clothing and other needs to

help ease the situation. Helping her

family didn’t stop there. She sent a

large number solders and knights from Caithness, Orkney and Norway to fight for

her brother Robert.

Isabel, once again, took a strong

hand in arranging a marriage for her daughter.

At this point the tales of two Isabels turns into a tale of two Ingebjørgs. Isabel’s daughter named Ingebjørg, and her

niece also named Ingebjørg, were married to the younger sons of Erik, Duke of

Södermanland. Isabel’s daughter married Valdemar,

Duke of Finland, Uppland, and Öland.

Isabel was likely proud of the marriage, but that pride was dashed

before too long, leaving her daughter a young window, just as she had

been. The two Swedish princes had long

been mistrusted by their elder brother, King Birger, and eventually, in 1317 he

had them both arrested at a banquet at Nyköping Castle. They were held in a dungeon and no one was

allowed to see them. Sometime after January 1318, tides of their demise spread

throughout the country—rumors fearing they had been starved to death. Their widows, the Duchesses Ingebjørg, were

not meek in their acceptance of the deaths, instead became the leaders of their

husbands’ supporters. Eventually, later that year, they were able to force King Birger into exile, and crowned Magnús,

the son of Ingebjørg Håkonsdatter, as king of Sweden. Then, he succeeded his grandfather, Håkon V,

as king of Norway in 1319. The regency

was held by Magnús’ mother and grandmother, and Ingebjørg Eiriksdatter also

held a seat on the regency council.

In 1357, Ingebjørg died, naming

her mother as one of her heirs, increasing Isabel’s wealth. Isabel still did not return to Scotland. There is not a single instance recorded of

her returning to her family in the country where she was born. Instead, she lived in Bergen the remainder of

her life. On 13 April 1358 and at the

age of 86, she died in Bergen, Hordaland, Norway. Isabel finally returned to the soil of her

birth, being buried in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland.

Above: the first folio from an

Old French version of William of Tyre’s

“Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum”, which belonged to

Isabel Bruce, and the ex libris announcing her ownership is in red ink across

the top of the page.

In summarizing, these two

daughters of Marjorie Carrick may have shared a name, one common to the family,

but they and their lives couldn’t have been more different, each carving out a

special niche in history.

Next month, I will finish up with the remaining Bruce sisters—

Mary, Margaret and Maud.

Then in October I will turn my attention to

the Daughters of Bruce...

first up will be Marjorie Bruce Stewart,

the daughter of a king and the mother of a king

Deborah writes a Scottish Medieval Historical series the Dragons of Challon

and Contemporary Paranormal Romance series the Sister of Colford Hall.