In Part 1 of my stories about the

Two Ladies of Dunbar, I covered the

valiant Marjorie Comyn, countess of Dunbar and March. She married into the ancient Dunbar family,

and yet she held her castle against the king of England in a time of war. Instead of that deed striking a heroic chord

in history, earning her immortality, her fate has been largely, frustratingly

buried. Her defiance is little noted

today. No poems about her, few people

ever recall her life, or her heroic audacity.

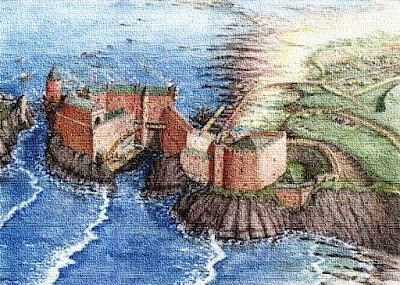

Castle Dunbar

Forty decades later, another woman traveled that same path. Agnes Randolph married into the Dunbar family—in fact, she married Marjorie’s son Cospatrick. By the time they wed, he was using Patrick as his given name. He was about eleven-years-old when his mother defended Dunbar Castle. Since young men of the nobility became squires around that age, I might assume he was riding at his father’s side, with the English king Edward I, and watched as his mother took a stance for the Scottish side. His young age is why his name isn’t on the Ragman Roll. Some mistakenly assert he assumed the titles to the earldoms in 1297, the year after his mother vanished from history. However, correspondence to and from king Edward during that time remark upon Patrick’s father’s and his loyalty to the crown, referencing the elder Dunbar as still in possession of the titles and keeping his oath to the English monarch. Edward won a crushing battle at Falkirk that autumn—with both Dunbars riding with him—yet it failed to bring him the control of the country he long craved. The castle of Dunbar—the name meaning fort of the point— was built on a huge promontory, which projected out into the sea. The ancient stronghold of the earls of March was of key strategic importance, due to its location being near to the major commercial seaport of Berwick. The fortress overlooked the coastal town of Dunbar, in East Lothian, and afforded defenders the view of most of southwest Scotland. Thus, Castle Dunbar was vital to Edward’s plans to defeating the Scots, once and for all.

Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfries

The center of the Scottish

resistance was Caerlaverock Castle, near Dumfries. The Comyns were still giving

the English soldiery, garrisoned throughout the countryside, hell and

fury. And the supposed highly defensible

Caerlaverock was their base for the struggle.

From there, they could launch surprise attacks, fighting in the Highland

way of guerilla warfare—strike and then vanish into the mists. Their familiarity of the countryside, and the

English troops' lack of it, gave them a distinct advantage. And the tactics proved to be a festering

thorn in Edward’s side. To that aim, he

fixed on denying the Scots this base of operations. Edward and his army advanced through

Annandale—lands of the Bruces—stopping off at the royal Pele Tower of

Lochmaben. The full splendor of

Longshanks' army bore down upon the beautiful moated castle, and with banners

flying high, he laid siege. Once again, riding at his side was Cospatrick of

Dunbar and his son Patrick. You can

read about the siege in the Song of Caerlaverock, an overly flowery poem that

is mostly PR for the English view of what happened. Even so, it is valuable to historians as it

notes the names of the many knights and lords who were there.

There were many rich caparisons embroidered on silks and satins; many a beautiful pennon fixed to a lance; and many a banner displayed. And afar off was the noise heard of the neighing of horses: mountains and valleys were everywhere covered with sumpter horses and wagons with provisions, and sacks of tents and pavilions. And the days were long and fine.

Touches,

chevalier of worship, carried gules with yellow martlets. Banner gules, a lion

argent, there the Earl of Lennox flew, and upon a silver border roses

of the field’s same hue; Patrick of Dunbar, his son, bore likewise with a

label blue.

The anonymous poet made the whole affair sound so gay, and what a valiant effort it was on the English’s part to invest the castle. In truth, the fortress was hardly a match for the English forces, so soon both Patrick and his father were back to their own business. By December, 1300, Patrick, now in his twenties, was named in an English Royal Administration paper, indicating he received regular payments for assisting King Edward in controlling the Scots in East Lothian.

Sometime after that point, he

married his first wife, Ermengarde Soulis.

Little is known of Ermengarde, other than she was a few years younger

than Patrick, and likely a cousin, the daughter of Sir William de Soulis (one

of the claimants to the throne of Scotland in 1296) and Ermengarde de

Duward. She gave birth to a son

Patrick—yes, yet another Patrick—sometime around 1304, for it was recorded that

she received a shipment of a cask of wine from Edward Longshanks, and it was

noted she was pregnant at the time. There was another son, John, born less than

two years later. After that, nothing

else is heard about her. No reference to

her death. No place of burial, though one

would assume at Dunbar Castle, which is now in ruins. One might infer she died in childbirth, or

shortly thereafter, as the date would indicate that.

In 1305, Patrick petitioned King

Edward for his father's lands at Polwarth, Berwickshire to be settled upon him,

but this was declined. Against the

backdrop of February 1306, Robert Bruce called for a meeting with John “Red”

Comyn. Both had been Guardians of

Scotland. Both held no love loss for the

other. And both wanted to be king of the

Scots. Instead of coming to an

agreement, Bruce killed Comyn, and a month later then declared himself

king. Early 1307, Edward was making

plans, once more, to invade Scotland. He

commanded, Patrick, along with his aging father (now sixty-five), were to

preserve the peace in Scotland and to obey the earl of Richmond in this

aim. The denial of his petition in 1305

had little consequences or impact to Patrick.

Edward I died in July of 1307.

Less than a year later saw Cospatrick die, so his heir Patrick assumed

the earldoms of Dunbar and March.

In 1313, Patrick was sent to

England with a petition for the new king—Edward II. The communication was from people of

Scotland, laying out their suffering at the hands of Edward Bruce. Robert’s younger brother had a bone to pick

with the Comyns and Dunbars and seemed to take great pleasure in the

confiscating coin, crops and horses from his enemy. Patrick’s own lands

and those of his vassals were vulnerable to raids of both Bruces, as well as by

attacks by the English garrisons at Berwick and Roxburgh. I surmise, in order to protect his honours,

Patrick did his best to keep both sides in reasonable humor with him. When the Battle of Bannockburn in 1313 was a

route for the Scots, Patrick provided shelter and assistance to the fleeing

English king.

No sooner than Edward II was

safely across the English border, Patrick switched sides, aligning himself with

Robert the Bruce in spectacular fashion.

He took part in the Scottish siege at Berwick, as one of Bruce’s commanders.

He helped Bruce gain control of the town on the 28th of Mar

1318, and the castle by the 20th July of the same year. Bruce must have been pleased with Patrick’s

tireless efforts for he received a grant of lands from King Robert covering the

ones Patrick had been forced to forfeit in England due to the war.

He also received a new wife. And no miss to fade into the annals of history. His second wife was Agnes, daughter of Bruce’s nephew, Thomas Randolph, 1st earl of Moray. Their royal lineage goes back to Gospatrick of Dunbar, Somerland, King Duncan I and Pictish kings, and through his mother's side he was 8th great-grandson of Henry I, king of France. Though doubt has been cast by some historians about her father being Robert the Bruce's nephew it is easily proven. Bruce's older half-sister, Isabel du Kilconquhar was the mother of Thomas Randolph. Documents from the reign of David II of Scotland (Bruce's son) makes hundreds of references to John Randolph being his cognatus/consanguineus (kinsman/male cousin)-- a cousin of the first or second degree.

If Dunbar had been vital to the English’s ability to strike into the heart of Scotland, it was doubly as important in the Bruce’s mind. He was fighting to subdue Clan Comyn—which meant the largest part of Scotland—and preparing should Edward II invade yet again. The marriage between Patrick and Agnes had all the markings of a political union. Bruce got a strong ally against his old foes the Comyns—Patrick’s relatives—and Patrick checkmated Bruce’s generals Randolph and James Douglas from raiding his lands every time they needed supplies. The advantageous marriage seemed to seal the pact. They were married in England, due to Scotland being under interdict. In 1317, Pope John XXII issued the interdict because Bruce and Douglas kept raiding in England. The papal decree prevented Scotland’s churches from celebrating all sacred rites and ceremonies, save death—which meant no marriages could be performed there.

Agnes’ amazing father died in 1332 at the Battle of Musselburg. He didn't die in battle, but fell ill and died a short time later. Randolph was on his way to repeal yet another attack by the English. This time, it was Edward III backing the exiled Edward Balliol in his attempt to claim the Scottish crown. The latter was the son of John Balliol—the man Edward’s grandfather made king of the Scots in 1292. Both of them were pressing the assertion that Robert the Bruce had no true claim to the crown, that John was the last king of Scotland, and thus Edward Balliol, his son, was the real monarch.

During these years, Agnes held the important castle of Dunbar. She was the eldest child of Randolph’s children by his wife Isabel Stuart of Bonkyll. Agnes was a strong, opinionated female, and clearly had learned a lot from her resourceful father. She inherited her dark looks from her handsome sire. Often called "Black Annis" (a Scottish witch) or “Black Agnes”, historians immediately assume she was dark-complected, calling her “swarthy”. However, in Scottish Clans you will often see “black branch” and “red branch”, meaning the black line is the elder son, while the red branch is the younger son, so I question if the Scots calling her Black Agnes had more to do with the fact she was the eldest of Randolph’s children.

It must have chafed a

strong-willed Agnes that upon the death of her father, the title of earl of

Moray went to first her younger brother, instead of her. Thomas held the title for barely a year

before dying at the Battle of Daupin.

Then, it was handed to her second brother, John. Later on, after his demise, the title

reverted to the crown, but Agnes refused to accept that and added the Countess Moray

to her status. None dared challenge her

on this. Patrick began using the title as well. Her brother had married well to

Euphemia Ross; later, after his death she remarried to King Robert II of

Scotland. After Agnes’ death, Robert II

conferred the title officially to her nephew, George Dunbar (Isabella’s son)

since Agnes had no legitimate heirs. (This has been questioned and disputed by

historians, even to some listing George as their son).

Patrick was a good match in

ambition for Agnes. Sometime after 1331,

the Bishop of Durham complained to the Regency in Scotland

that the village of Upsettlington, on the Scottish side of the River

Tweed west of Norham, belonged to the See of Durham and “not the earl

of Dunbar, who had seized it”. Patrick

was not only a good fighter, but proved a savvy politician. Patrick was named as the Guardian of

Scotland, and upon his father-in-law’s death, replaced Randolph as regent for

Bruce’s young son, King David II.

Accounts differ about whether

Agnes and Patrick had and were survived by any children. That they didn’t seem to be confirmed since

their titles and inheritances passed to the children of the marriage between

Patrick's nephew and Agnes' sister. There is a claim (which doesn't square with

the way the earldom of Moray actually passed to the next generation),

suggesting that she did have a daughter, also called Agnes of Dunbar. In the years following, the other Agnes

became the mistress of David II, and preparations undertaken showed

she was his intended wife when he died in 1371.

Since Patrick was away so much, Agnes could have had a child by another

man, or possibly she was fostering the daughter of her sister, in Scottish

tradition. (One assertion is that Agnes

was Patrick’s daughter by his first wife—but even a small amount of research

invalidates that claim as the birth of this Agnes was after Patrick married

Randolph’s daughter).

To escape prison, Patrick bent

knee to the two Edwards, and was back on the English side. His presence is noted at the Scottish

parliament Edward Balliol held, in the role of the new king. No mention of Agnes being with her husband

was noted, so we may assume she was still at Dunbar and in charge of the

fortress. Balliol gave over the castles

Berwick, Dunbar, Roxburgh, and Edinburgh to Edward III as payment for his

help. Likely a furious Agnes was forced

to watch her husband destroy much of Dunbar Castle’s fortifications as part of

the agreement, rendering it useless to the Scottish forces. No sooner than the dismantling was

accomplished, Edward III contrarily changed his mind and demand Patrick rebuild

and refit Dunbar—and pay for all the refortifications out of his own

pocket. The castle wouldn’t be battle

ready again until late 1337. A change

in decision, which would soon come to haunt Edward III.

On 13th January 1338,

when Patrick Dunbar was away, the English, under William Montague, 1st earl of

Salisbury, laid siege to Dunbar Castle.

They made the mistake of assuming it would be an easy task since Lady

Dunbar was in residence with only her servants and a few guards. However, Agnes

was determined not to surrender the fortress, even though facing the English’s

vastly superior force of 20,000 men. Salisbury

must have been flabbergasted as Agnes tossed down her firm No! from the rampart

and answered the demand:

"Of

Scotland's King I haud my house, I pay him meat and fee, And I will keep my

gude auld house, while my house will keep me."

Don’t you think Agnes was just a tad upset? They had just finished rebuilding the castle on Edward III’s command, and he turned around and decided to lay siege to it? Clearly, Agnes was not about to hand it over to Edward’s lackey, just to appease the king’s current whim. Enough was enough! It appears she was caught unawares by the attack. The castle guard had been thinned, the Dunbar men off fighting with her husband, and since it was midwinter, supplies were running low. Agnes was not prepared to withstand a long siege, but withstand she did.

When the earl didn’t hesitate in launching the machine, Agnes had boulders—the very ones the English had been flinging into the castle—dropped over the ramparts from a crane and onto the sow, crushing it. She, naturally, shouted thanks to Salisbury for the ammunition he had supplied Dunbar. As the survivors scurried back to the English line, Agnes launched another taunt with her indelicate wit:

“…behold the litter of English pigs scurrying!”

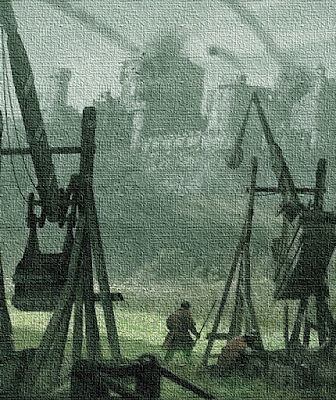

a Sow

Her joyful

defiance seemed to infect the meager number of guards. One Dunbar archer drew down on Salisbury, but

deliberately hit the man next to him, and then yelled:

"There comes one of my lady's tire pins; Agnes' love shafts go straight to the heart."

Obviously, all the work Patrick had done over the past three years to refortify Dunbar was well worth the coin it cost. It was impossible for the English to invest the castle. Unable to make any progress with the attacks, Salisbury switched to guile. He bribed a Scotsman, who guarded the portcullis at the front of the castle. Salisbury extracted a promise to leave the gate unsecure, so his troops could descend upon the mighty gate and force their way inside the bailey before alarm could be raised. The earl must have smirked when the man accepted the bribe, and a short time later the portcullis creaked open. In true careless fashion, the English troops charged the gate, with Salisbury in the lead. One of his eager soldiery dashed past him and through the entry first. Shock filled them when the portcullis came crashing down, trapping the eager Englishman on the Scottish side. Salisbury just missed being captured by Agnes! The gatekeep had accepted the bribe, but had run straight to Agnes with the tale of what Salisbury wanted him to do. She had turned the tables and laid a trap for the haughty earl. Sadly, she missed taking him prisoner, but she couldn’t resist another of her stinging barbs:

"Farewell, Montague, I intended that you

should have supped with us, and assist us in defending the Castle against the

English."

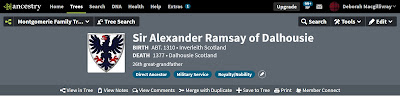

Winter passed, then spring, and summer was

upon them. Salisbury knew the castle had

to be rationing food and water. So, he

turned his attention to the longer means of winning a siege—a blockade to

starve the castle out. He cut off all

roads, paid Genoese galleys to block the defenders from receiving support from

the sea, and stopping any communication with the outside world. Only Sir Alexander of Dalhousie (my 26th great-grandfather)—who had earned a reputation for being a constant thorn in

the English king's side—got wind of Agnes’ predicament. He left Edinburgh, and with forty men, moved

swiftly up the coast. Ramsay and his

small company approached the castle in the cover of night, and entered through

the postern gate from the sea. He

brought fresh troops, ready and eager to fight, and food for the people of

Dunbar. Salisbury, expecting a weakened

guard, launched another frontal assault on the castle. However, Ramsay rushed out with his hardened

troops, and pushed the startled Englishmen back all the way to their

encampment.

Agnes had held Dunbar for nearly

five months. With Salisbury becoming a

laughing stock and no closer to forcing her surrender, on the 10th of June

1338, he threw up his hands and lifted the siege. The triumph of Agnes over the earl and 20,000

English men lives on in a poem by Sir Walter Scott, which put a rhyme in the

earl’s mouth…

She

kept a stir in tower and trench

That brawling, boisterous Scottish wench;

Came I early, came I late,

I found Agnes at the gate

The failed siege of Dunbar had

cost the English crown nearly 6,000 British pounds and gained nothing from it

but mockery. It seemed Edward III was no

more successful in subduing Scotland than his father and grandfather had

been. But Agnes, the heroine of the

Scots, had earned immortality in history with her valiant defiance.

George Dunbar must have inherited

the traits of the Randolph family, because he rose to become one of the most

powerful men in Scotland. But no one

wrote sagas and poems about him. They

even wrote a song about her.